In This Sky, the Planes Fly Alone

By MALIA WOLLAN

Published: May 15, 2011

BOULDER, Colo. — A father of five and a professed geek, Chris Anderson, editor in chief of Wired magazine, is always looking for child-friendly activities that could, he hopes, inculcate his children with techie sensibilities.

So one weekend in 2007, Mr. Anderson brought home a model radio-controlled airplane and a Lego Mindstorms robotics kit. Soon he and the children put the two toys together, making the Lego robot fly the plane. The result was a clunky Lego drone.

His children moved on to other playthings. But Mr. Anderson was captivated. And that led him to found an online network for amateur drone enthusiasts, DIY Drones, and to co-found a new business, 3D Robotics, which features an online store for those hobbyists.

“This is the future of aviation,” Mr. Anderson, 49, said. “Our children will not believe that people used to drive cars and drive airplanes. We are the weak link in the chain.”

Unlike traditional radio-controlled planes, unmanned aerial vehicles, or U.A.V.’s, have the capacity for autonomous flight and navigation. A radio-controlled plane becomes an autonomous drone when it is given an autopilot, which Mr. Anderson calls “giving the plane a brain.”

Mr. Anderson was among the enthusiasts here recently attending the third annual Autonomous Vehicle Competition, where teams of software programmers and robot tinkerers from across the country faced off in robot races.

Though many of the racers focused on antics like dressing their robots as dinosaurs, Mr. Anderson believes that unmanned aircraft are not just for fun-loving hobbyists. He argues that small drones outfitted with sensors could be used to assess emergency situations like that at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, to find survivors of natural disasters, to assist law enforcement and to monitor pipelines, agricultural crops and wildlife populations.

He is not alone in his thinking; many companies and research institutions are working to design drones for commercial and other uses. The Federal Aviation Administration estimates that around 50 companies, universities and government organizations are at work on at least 155 drone designs in the United States alone. Some companies already manufacture sophisticated drones. AeroVironment, based in Monrovia, Calif., designed the 4.2-pound, hand-launched Raven aircraft currently used by United States military forces in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Still, there are privacy and safety concerns, which the F.A.A. mitigates by limiting commercial opportunities for U.A.V.’s and by requiring special permits for unmanned vehicles to fly in the National Airspace System — a complex web of more than 19,000 airports that involves about 100,000 flights a day and thousands of air traffic controllers.

So far, the agency has issued 240 such permits — the Department of Homeland Security received permission to patrol the border with drones, and NASA was allowed to fly unmanned aircraft to spot wildfires across the West.

The F.A.A. has an additional 164 permit applications pending, and early this fall expects to release new rules, which Mr. Anderson hopes will be more lenient toward unmanned aircraft.

Mr. Anderson said DIY Drones had 15,000 members and had about one million page views a month, tapping into a world of do-it-yourself hobbyists who build their own small drones and fly them around parks and neighborhoods. Many of the site’s members, he said, work day jobs at major technology companies like Apple and work in their off hours to develop open-source software that can fly seagull-size drones.

Mr. Anderson founded 3D Robotics with Jordi Muñoz, 24. The two met soon after Mr. Anderson trolled the Web for fellow homegrown drone makers and saw a video of Mr. Muñoz flying a helicopter using a repurposed Wii controller. The company now sells the autopilot hardware, cords and sensors needed to build unmanned planes and quadcopters, small helicopters with four rotors.

“We are growing really fast,” said Mr. Muñoz, the company’s chief executive, who assembled early prototypes at his home. “When we first started I was working 24 hours a day, seven days a week for almost a year.”

The company opened a manufacturing facility in San Diego, which now employs 14 people to assemble and ship drone parts. Last year, the company had a 20 percent increase in sales every month, the founders said, with total sales over $1 million. Customers pay about $300 for an autopilot that includes a GPS device, accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers and all the gadgetry necessary to turn a model plane into an autonomous drone.

Under F.A.A. guidelines, recreational fliers like Mr. Anderson and his customers must keep unmanned aircraft lower than 400 feet, away from other aircraft and within the operator’s sight.

Nicholas Roy, an associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, works with students to build the software to run small-scale drones that do not rely on GPS equipment, which is often faulty indoors and in cities — what Mr. Roy calls an “urban canyon.”

“In terms of understanding what it means to operate in the physical world with intelligence, unmanned aerial vehicles are a fantastic way to do that,” said Mr. Roy, who also leads M.I.T.’s Robust Robotics Group.

But he has some reservations about the widespread use of drones.

“It’s easy to say, these things are so small, what damage can they do?” he said. “But they can carry an awful lot of energy and they can accumulate energy very quickly. When one comes out of the sky and hits the ground the potential for real damage is there.”

Others emphasize the privacy concerns.

“The hobbyists are of less concern from a privacy perspective, but I am worried about surveillance of certain parts of cities by law enforcement using drones as though we were somehow in the theater of war,” said Ryan Calo, director of the Consumer Privacy Project at Stanford Law School. “And I’m worried about the inadequacy of privacy law at a constitutional and subconstitutional level to deal with that.”

But, at the drone event, Mr. Anderson and Mr. Muñoz seemed most concerned with keeping their aircraft dry and airborne despite the snow flurries.

“No guts, no glory,” said Mr. Anderson, who expected some drones to crash.

After a day of sputtering failures and spectacular and often unpredictable flights, first place in the aerial category went to Antonio Liska, a 29-year-old aerospace engineer who hopes to start a business selling drones. He programmed his own autopilot and plans to fly his unmanned aircraft into volcanoes in Central America — “just because I can,” he said.

US Navy drones: Coming to a carrier near China?

Posted 5/16/2011 1:56 PM ET

By Eric Talmadge, Associated Press

YOKOSUKA, Japan — The U.S. is developing aircraft carrier-based drones that could provide a crucial edge as it tries to counter China's military rise.

American officials have been tightlipped about where the unmanned armed planes might be used, but a top Navy officer has told The Associated Press that some would likely be deployed in Asia.

"They will play an integral role in our future operations in this region," predicted Vice Adm. Scott Van Buskirk, commander of the U.S. 7th Fleet, which covers most of the Pacific and Indian oceans.

Land-based drones are in wide use in the war in Afghanistan, but sea-based versions will take several more years to develop. Northrop Grumman conducted a first-ever test flight -- still on land -- earlier this year.

Van Buskirk didn't mention China specifically, but military analysts agree the drones could offset some of China's recent advances, notably its work on a "carrier-killer" missile.

"Chinese military modernization is the major long-term threat that the U.S. must prepare for in the Asia-Pacific region, and robotic vehicles -- aerial and subsurface -- are increasingly critical to countering that potential threat," said Patrick Cronin, a senior analyst with the Washington-based Center for New American Security.

China is decades away from building a military as strong as America's, but it is developing air, naval and missile capabilities that could challenge U.S. supremacy in the Pacific -- and with it, America's ability to protect important shipping lanes and allies such as Japan and South Korea.

China maintains it does not have offensive intentions and is only protecting its own interests: The shipping lanes are also vital to China's export-dependent economy. There are potential flash points, though, notably Taiwan and clusters of tiny islands that both China and other Asian nations claim as their territory.

The U.S. Navy's pursuit of drones is a recognition of the need for new weapons and strategies to deal not only with China but a changing military landscape generally.

"Carrier-based unmanned aircraft systems have tremendous potential, especially in increasing the range and persistence of our intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance operations, as well as our ability to strike targets quickly," Van Buskirk said at the 7th Fleet's headquarters in Yokosuka, Japan.

His fleet boasts one carrier -- the USS George Washington -- along with about 60 other ships and 40,000 sailors and Marines.

Experts say the drones could be used on any of the 11 U.S. carriers worldwide and are not being developed exclusively as a counterbalance to China.

But China's reported progress in missile development appears to make the need for them more urgent.

The DF 21D "carrier killer" missile is designed for launch from land with enough accuracy to hit a moving aircraft carrier at a distance of more than 900 miles (1,500 kilometers). Though still unproven -- and some analysts say overrated -- no other country has such a weapon.

Current Navy fighter jets can only operate about 500 nautical miles (900 kilometers) from a target, leaving a carrier within range of the Chinese missile.

Drones would have an unrefueled combat radius of 1,500 nautical miles (2,780 kilometers) and could remain airborne for 50 to 100 hours -- versus the 10 hour maximum for a pilot, according to a 2008 paper by analysts Tom Ehrhard and Robert Work at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Work is now an undersecretary of the Navy.

"Introducing a new aircraft that promises to let the strike group do its work from beyond the maximum effective firing range of the anti-ship ballistic missile -- or beyond its range entirely -- represents a considerable boost in defensive potential for the carrier strike group," said James Holmes of the U.S. Naval War College.

Northrop Grumman has a six-year, $635.8 million contract to develop two of the planes, with more acquisitions expected if they work. A prototype of its X-47B took a maiden 29-minute flight in February at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Initial testing on carriers is planned for 2013.

Other makers including Boeing and Lockheed are also in the game. General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, Inc. -- the maker of the Predator drones used in the Afghan war -- carried out wind tunnel tests in February. Spokeswoman Kimberly Kasitz said it was too early to divulge further details.

Some experts warn carrier-based drones are still untested and stress that Chinese advances have not rendered carriers obsolete.

"Drones, if they work, are just the next tech leap. As long as there is a need for tactical aviation launched from the sea, carriers will be useful weapons of war," said Michael McDevitt, a former commandant of the National War College in Washington, D.C., and a retired rear admiral whose commands included an aircraft carrier battle group.

Some analysts also note that China may be reluctant to instigate any fighting that could interfere with its trade.

Nan Li, an expert at the U.S. Naval War College's China Maritime Studies Institute, doubts China would try to attack a U.S. carrier.

"I am a skeptic of such an interpretation of Chinese strategy," he said. "But I do think the X-47B may still be a useful preventive capability for worst-case scenarios."

The Air Force and Navy both sponsored a project to develop carrier-based drones in the early 2000s, but the Air Force pulled out in 2005, leaving the Navy to fund the research.

Adm. Gary Roughhead, chief of naval operations, said last summer that the current goal of getting a handful of unmanned bombers in action by 2018 is "too damn slow."

"Seriously, we've got to have a sense of urgency about getting this stuff out there," he told a conference. "It could fundamentally change how we think of naval aviation."

Stealth drones monitored bin Laden

May. 18, 2011 12:00 AM

Washington Post

WASHINGTON - The CIA employed sophisticated new stealth drone aircraft to fly dozens of secret missions deep into Pakistani airspace and monitor the compound where Osama bin Laden was killed, current and former U.S. officials said.

Using unmanned planes designed to evade radar detection and operate at high altitudes, the agency conducted clandestine flights over the compound for months before the May 2 assault in an effort to capture high-resolution video that satellites could not provide.

The aircraft allowed the CIA to glide undetected beyond the boundaries that Pakistan has long imposed on other U.S. drones, including the Predators and Reapers that routinely carry out strikes against militants near the border with Afghanistan.

The agency turned to the new stealth aircraft "because they needed to see more about what was going on" than other surveillance platforms allowed, said a former U.S. official familiar with the details of the operation. "It's not like you can just park a Predator overhead - the Pakistanis would know," added the former official, who, like others interviewed, spoke on the condition of anonymity, citing the sensitivity of the program.

The monitoring effort also involved satellites, eavesdropping equipment and CIA operatives based at a safe house in Abbottabad.

Drones on the home front

SourceUnmanned aircraft, which have already revolutionized warfare in Iraq and Afghanistan, are entering U.S. airspace. While drones have already been used to patrol the border and track forest fires, their most controversial use may be as surveillance tools for federal, state and local law enforcement.

Draganflyer X6

Draganfly Innovations

The remotely operated miniature helicopter is designed to carry wireless video, still cameras and light thermal imaging equipment. It is used by the Mesa County, Colo., Sheriff's Office.

Specifications

Endurance: 20 minutes

Max. altitude: 8,000 feet

Max. speed: 30 mph

Propulsion: Six propellers powered by 14.8 V electrical motors

Dimensions

The Draganflyer is three feet wide and nearly as long, and it weighs 53 ounces.

Predator B

General Atomics

The aircraft can carry a wide array of surveillance equipment and be piloted remotely or be programmed to fly a set flight plan. It is being used by the Department of Homeland Security to patrol the U.S. border.

Dimensions

The Predator B has a wingspan of 66 feet and a length of 36 feet.

Specifications

Endurance: 30 hours

Max. altitude: 50,000 feet

Max. speed: 243 mph

Payload: Up to 3,000 pounds

Propulsion: Single TPE-331-10 turboprop engine

T-Hawk

Honeywell

The micro air vehicle can be deployed vertically in less than 10 minutes and carry up to 20 pounds of equipment to capture 24 minutes of high-quality video. It is used by the Miami-Dade County, Fla., Police Department.

Specifications

Endurance: 50 minutes

Max. altitude: 10,000 feet

Max. speed: 46 mph

Propulsion: Gasoline piston engine

Dimensions

The T-Hawk is approximately two feet tall and weighs 17.5 pounds.

Wasp

AeroVironment

The hand-launched micro-drone can be remotely operated or fly a programmed flight plan. It has two high-resolution cameras and an infrared imager. It is used by the Texas Department of Public Safety.

Specifications

Endurance: 45 minutes

Max. altitude: 1,000 feet

Max. speed: 40.3 mph

Propulsion: Propeller powered by a small electrical motor

Electric-powered radio control planes are taking off

Electric-powered radio-control planes taking off

By Cyndia Zwahlen

June 6, 2011

When Greg Stone flies his model airplanes in Irvine at Orange County Great Park — fittingly on the site of the former El Toro Marine Corps Air Station — he's surrounded by the buzz of the tiny electric motors that power his planes and those of fellow hobbyists.

It's a sharp contrast to when fuel-powered model planes — which were much louder, as well as faster than the electric models — dominated the hobby.

The radio-controlled electric planes, powered by lightweight, rechargeable batteries, have become increasingly popular with model aviation buffs who want an alternative to traditional fuel-powered models.

"It's a shift I made in the last two years," said Stone, president of the Orange Coast Radio Control Club and a veteran model aviator. "And we have been seeing more families, more youths, everybody, getting into it."

Fuel-powered planes, including gasoline, nitro and even jet-fueled models, still have many devoted followers. But demand for the cleaner and quieter electric planes, which are called park fliers, has grown.

Businesses that sell the planes and parts hope that it will provide a boost to the long-stagnant hobby.

"Most of what we are selling is electric," said Larry Thompson, who employs 20 people at the Pegasus Hobbies store in Montclair.

A few years ago, park fliers accounted for "30% of sales, but now it's closer to 70%," said Robert Holick, the new owner of Landing Products Inc. in Woodland, Calif. His five-person company has made the well-known Advance Precision Composites model airplane propellers since 1989.

The small park fliers are easier to fly because they can go slower, without sacrificing maneuverability, he said. Innovations in materials, including bodies made of newer, sturdier foam and fast-drying glues, have made them easier and less expensive to fix.

"Now you can fly at 20 mph, so you can learn," said Thompson, who co-owns the store with Tom Macomber. "When you crash, 75% of crashes are going to cost you $20 or less to fix."

Lower costs and better performance have also been brought about by advances in the motors and electronic controls for the planes.

So far, it's unclear whether the park fliers are going to help businesses soar.

Attendance at a recent consumer show in Ontario sponsored by the Academy of Model Aeronautics was 5,200, spokesman Chris Brooks said. But that was about the same number as last year.

The average age of AMA numbers, the nonprofit group said, is 58.

"The hobby itself seems to be pretty stagnant," said Shawn Spiker, sales manager at Hitec RCD USA Inc., an 18-person plane and parts distributor based in Poway, Calif.

The hope is that park fliers "will bring in younger people to kind of replenish the people in it," said Mark Schwing, owner of Electronic Model Systems in Yorba Linda and president of the Radio Control Division Council of the Hobby Manufacturers Assn., which is based in Butler, N.J.

The academy created a new, lower-cost membership category for park fliers called the Park Pilot program. It has signed up 2,070 people, Brooks said. The group has also launched a quarterly magazine devoted to park pilots.

"We are looking at the tip of the iceberg," said the magazine's editor, Jeff Troy.

smallbiz@latimes.com

Drones - Cool high tech stuff to kill people with

Drones - Cool high tech stuff!But does American really need to be at war with everybody else in the world and spend gazillions of taxpayer dollars on these high tech war toys we use to kill brown skinned people through out the world?

I don't think so!

"More than 1,900 insurgents in Pakistan’s tribal areas have been killed by American drones since 2006" - I suspect a large number of these people murdered by the American government were innocent civilians. In Vietnam the government considered anybody with brown skin that was killed to be a member of the Viet Cong. I suspect in Iraq and Afghanistan the term insurgent is used to apply to any brown skin folks killed by the American Empire.

War Evolves With Drones, Some Tiny as Bugs

By ELISABETH BUMILLER and THOM SHANKER

Published: June 19, 2011

WRIGHT-PATTERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Ohio — Two miles from the cow pasture where the Wright Brothers learned to fly the first airplanes, military researchers are at work on another revolution in the air: shrinking unmanned drones, the kind that fire missiles into Pakistan and spy on insurgents in Afghanistan, to the size of insects and birds.

The base’s indoor flight lab is called the “microaviary,” and for good reason. The drones in development here are designed to replicate the flight mechanics of moths, hawks and other inhabitants of the natural world. “We’re looking at how you hide in plain sight,” said Greg Parker, an aerospace engineer, as he held up a prototype of a mechanical hawk that in the future might carry out espionage or kill.

Half a world away in Afghanistan, Marines marvel at one of the new blimplike spy balloons that float from a tether 15,000 feet above one of the bloodiest outposts of the war, Sangin in Helmand Province. The balloon, called an aerostat, can transmit live video — from as far as 20 miles away — of insurgents planting homemade bombs. “It’s been a game-changer for me,” Capt. Nickoli Johnson said in Sangin this spring. “I want a bunch more put in.”

From blimps to bugs, an explosion in aerial drones is transforming the way America fights and thinks about its wars. Predator drones, the Cessna-sized workhorses that have dominated unmanned flight since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, are by now a brand name, known and feared around the world. But far less widely known are the sheer size, variety and audaciousness of a rapidly expanding drone universe, along with the dilemmas that come with it.

The Pentagon now has some 7,000 aerial drones, compared with fewer than 50 a decade ago. Within the next decade the Air Force anticipates a decrease in manned aircraft but expects its number of “multirole” aerial drones like the Reaper — the ones that spy as well as strike — to nearly quadruple, to 536. Already the Air Force is training more remote pilots, 350 this year alone, than fighter and bomber pilots combined.

“It’s a growth market,” said Ashton B. Carter, the Pentagon’s chief weapons buyer.

The Pentagon has asked Congress for nearly $5 billion for drones next year, and by 2030 envisions ever more stuff of science fiction: “spy flies” equipped with sensors and microcameras to detect enemies, nuclear weapons or victims in rubble. Peter W. Singer, a scholar at the Brookings Institution and the author of “Wired for War,” a book about military robotics, calls them “bugs with bugs.”

In recent months drones have been more crucial than ever in fighting wars and terrorism. The Central Intelligence Agency spied on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan by video transmitted from a new bat-winged stealth drone, the RQ-170 Sentinel, otherwise known as the “Beast of Kandahar,” named after it was first spotted on a runway in Afghanistan. One of Pakistan’s most wanted militants, Ilyas Kashmiri, was reported dead this month in a C.I.A. drone strike, part of an aggressive drone campaign that administration officials say has helped paralyze Al Qaeda in the region — and has become a possible rationale for an accelerated withdrawal of American forces from Afghanistan. More than 1,900 insurgents in Pakistan’s tribal areas have been killed by American drones since 2006, according to the Web site www.longwarjournal.com.

In April the United States began using armed Predator drones against Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi’s forces in Libya. Last month a C.I.A.-armed Predator aimed a missile at Anwar al-Awlaki, the radical American-born cleric believed to be hiding in Yemen. The Predator missed, but American drones continue to patrol Yemen’s skies.

Large or small, drones raise questions about the growing disconnect between the American public and its wars. Military ethicists concede that drones can turn war into a video game, inflict civilian casualties and, with no Americans directly at risk, more easily draw the United States into conflicts. Drones have also created a crisis of information for analysts on the end of a daily video deluge. Not least, the Federal Aviation Administration has qualms about expanding their test flights at home, as the Pentagon would like. Last summer, fighter jets were almost scrambled after a rogue Fire Scout drone, the size of a small helicopter, wandered into Washington’s restricted airspace.

Within the military, no one disputes that drones save American lives. Many see them as advanced versions of “stand-off weapons systems,” like tanks or bombs dropped from aircraft, that the United States has used for decades. “There’s a kind of nostalgia for the way wars used to be,” said Deane-Peter Baker, an ethics professor at the United States Naval Academy, referring to noble notions of knight-on-knight conflict. Drones are part of a post-heroic age, he said, and in his view it is not always a problem if they lower the threshold for war. “It is a bad thing if we didn’t have a just cause in the first place,” Mr. Baker said. “But if we did have a just cause, we should celebrate anything that allows us to pursue that just cause.”

To Mr. Singer of Brookings, the debate over drones is like debating the merits of computers in 1979: They are here to stay, and the boom has barely begun. “We are at the Wright Brothers Flier stage of this,” he said.

A tiny helicopter is buzzing menacingly as it prepares to lift off in the Wright-Patterson aviary, a warehouse-like room lined with 60 motion-capture cameras to track the little drone’s every move. The helicopter, a footlong hobbyists’ model, has been programmed by a computer to fly itself. Soon it is up in the air making purposeful figure eights.

“What it’s doing out here is nothing special,” said Dr. Parker, the aerospace engineer. The researchers are using the helicopter to test technology that would make it possible for a computer to fly, say, a drone that looks like a dragonfly. “To have a computer do it 100 percent of the time, and to do it with winds, and to do it when it doesn’t really know where the vehicle is, those are the kinds of technologies that we’re trying to develop,” Dr. Parker said.

The push right now is developing “flapping wing” technology, or recreating the physics of natural flight, but with a focus on insects rather than birds. Birds have complex muscles that move their wings, making it difficult to copy their aerodynamics. Designing insects is hard, too, but their wing motions are simpler. “It’s a lot easier problem,” Dr. Parker said.

In February, researchers unveiled a hummingbird drone, built by the firm AeroVironment for the secretive Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which can fly at 11 miles per hour and perch on a windowsill. But it is still a prototype. One of the smallest drones in use on the battlefield is the three-foot-long Raven, which troops in Afghanistan toss by hand like a model airplane to peer over the next hill.

There are some 4,800 Ravens in operation in the Army, although plenty get lost. One American service member in Germany recalled how five soldiers and officers spent six hours tramping through a dark Bavarian forest — and then sent a helicopter — on a fruitless search for a Raven that failed to return home from a training exercise. The next month a Raven went AWOL again, this time because of a programming error that sent it south. “The initial call I got was that the Raven was going to Africa,” said the service member, who asked for anonymity because he was not authorized to discuss drone glitches.

In the midsize range: The Predator, the larger Reaper and the smaller Shadow, all flown by remote pilots using joysticks and computer screens, many from military bases in the United States. A Navy entry is the X-47B, a prototype designed to take off and land from aircraft carriers automatically and, when commanded, drop bombs. The X-47B had a maiden 29-minute flight over land in February. A larger drone is the Global Hawk, which is used for keeping an eye on North Korea’s nuclear weapons activities. In March, the Pentagon sent a Global Hawk over the stricken Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in Japan to assess the damage.

A Tsunami of Data

The future world of drones is here inside the Air Force headquarters at Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Va., where hundreds of flat-screen TVs hang from industrial metal skeletons in a cavernous room, a scene vaguely reminiscent of a rave club. In fact, this is one of the most sensitive installations for processing, exploiting and disseminating a tsunami of information from a global network of flying sensors.

The numbers are overwhelming: Since the Sept. 11 attacks, the hours the Air Force devotes to flying missions for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance have gone up 3,100 percent, most of that from increased operations of drones. Every day, the Air Force must process almost 1,500 hours of full-motion video and another 1,500 still images, much of it from Predators and Reapers on around-the-clock combat air patrols.

The pressures on humans will only increase as the military moves from the limited “soda straw” views of today’s sensors to new “Gorgon Stare” technology that can capture live video of an entire city — but that requires 2,000 analysts to process the data feeds from a single drone, compared with 19 analysts per drone today.

At Wright-Patterson, Maj. Michael L. Anderson, a doctoral student at the base’s advanced navigation technology center, is focused on another part of the future: building wings for a drone that might replicate the flight of the hawk moth, known for its hovering skills. “It’s impressive what they can do,” Major Anderson said, “compared to what our clumsy aircraft can do.”

Published: June 19, 2011

The Changing Shapes of Air Power

Drones are playing an increasingly important role in the American military. Only 10 years ago, the Pentagon had about 50 drones; now there are 7,000 drones in its inventory, ranging in size from large blimps to tiny Hummingbirds. Here are 10 drones currently on the battlefield or on the drawing board.

Aerostat

200 ft. longAerostats are tethered fabric balloons filled with helium that float 15,000 feet in the air from a single cable. They can lift 1,200 pounds, including a camera that pans 360 degrees for constant real-time surveillance. They are used extensively on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border and above Kabul, where one of them is anchored at Bala Hissar, an ancient fortress. Their virtue is that they can stay aloft for months at a time, carrying a heavy load of intelligence equipment. Their shortcoming is that they cannot be moved rapidly for new assignments.

65 ft. across the hull

Global hawk

44 ft. longSometimes described as a “flying albino whale,” the Global Hawk is the largest flying drone. Although linked to humans on the ground, Global Hawks fly mostly on their own, guided by GPS coordinates they download from satellites. They were deployed over Afghanistan in 2001, providing commanders with battlefield images. The Global Hawk flies higher than the Predator and can stay up longer — for almost two days.

116 ft. wingspan

X-47B

38 ft. longThe Navy’s prototype combat drone, and the first combat drone able to take off from an aircraft carrier and land on it. Its first test flight (29 minutes) was on Feb. 7, 2011.

62 ft. wingspan

Reaper

36 ft. longThe largest armed drone. Called a “hunter-killer” aircraft, the Reaper can detect humans and can fire Hellfire air-to-surface missiles. It will soon replace the better-known Predator.

66 ft. wingspan

Predator

27 ft. longThe Predator is the Cessna-size workhorse that has dominated remotely piloted flight since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. The Pentagon has 169 Predators in its inventory.

55 ft. wingspan

Fire scout

24 ft. longThe Fire Scout is designed to take off and land vertically. Last summer the operators of a Fire Scout drone lost control of it in the airspace over Washington, D.C.

27.5 ft. rotor diameter

Shadow

11.3 ft. longThe little sister to the Predator, the Shadow is launched by a catapult, rather than from a runway. The drone is used by Army and Marine forces in the field. The United States recently sold a number to Pakistan.

14 ft. wingspan

Raven

3 ft. longThe Raven, which weighs just five pounds, is launched into the air by tossing it like a football. It is carried by ground units in the field that need quick awareness of what may be around a corner.

4.5 ft. wingspan

Hummingbird

4 in. longThe prototype remote-controlled Hummingbird has a tiny camera in its belly and weighs less than two-thirds of an ounce. Propelled only by its flapping wings, it can fly at speeds up to 11 miles per hour, hover and perch on a windowsill.

6.5 in wingspan

Insect swarms

The drones of the future. Researchers say there could be swarms of dragonfly-size drones — or smaller — by 2030.

Global race on to match U.S. drone capabilities

By William Wan and Peter Finn, Monday, July 4, 9:42 AM

At the most recent Zhuhai air show, the premier event for China’s aviation industry, crowds swarmed around a model of an armed, jet-propelled drone and marveled at the accompanying display of its purported martial prowess.

In a video and map, the thin, sleek drone locates what appears to be a U.S. aircraft carrier group near an island with a striking resemblance to Taiwan and sends targeting information back to shore, triggering a devastating barrage of cruise missiles toward the formation of ships.

Little is known about the actual abilities of the WJ-600 drone or the more than two dozen other Chinese models that were on display at Zhuhai in November. But the speed at which they have been developed highlights how U.S. military successes with drones have changed strategic thinking worldwide and spurred a global rush for unmanned aircraft.

More than 50 countries have purchased surveillance drones, and many have started in-country development programs for armed versions because no nation is exporting weaponized drones beyond a handful of sales between the United States and its closest allies.

“This is the direction all aviation is going,” said Kenneth Anderson, a professor of law at American University who studies the legal questions surrounding the use of drones in warfare. “Everybody will wind up using this technology because it’s going to become the standard for many, many applications of what are now manned aircraft.”

Military planners worldwide see drones as relatively cheap weapons and highly effective reconnaissance tools. Hand-launched ones used by ground troops can cost in the tens of thousands of dollars. Near the top of the line, the Predator B, or MQ9-Reaper, manufactured by General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, costs about $10.5 million. By comparison, a single F-22 fighter jet costs about $150 million.

Defense spending on drones has become the most dynamic sector of the world’s aerospace industry, according to a report by the Teal Group in Fairfax. The group’s 2011 market study estimated that in the coming decade global spending on drones will double, reaching $94 billion.

But the world’s expanding drone fleets — and the push to weaponize them — have alarmed some academics and peace activists, who argue that robotic warfare raises profound questions about the rules of engagement and the protection of civilians, and could encourage conflicts.

“They could reduce the threshold for going to war,” said Noel Sharkey, a professor of artificial intelligence and robotics at the University of Sheffield in England. “One of the great inhibitors of war is the body bag count, but that is undermined by the idea of riskless war.”

China on fast track

No country has ramped up its research in recent years faster than China. It displayed a drone model for the first time at the Zhuhai air show five years ago, but now every major manufacturer for the Chinese military has a research center devoted to drones, according to Chinese analysts.

Much of this work remains secret, but the large number of drones at recent exhibitions underlines not only China’s determination to catch up in that sector — by building equivalents to the leading U.S. combat and surveillance models, the Predator and the Global Hawk — but also its desire to sell this technology abroad.

“The United States doesn’t export many attack drones, so we’re taking advantage of that hole in the market,” said Zhang Qiaoliang, a representative of the Chengdu Aircraft Design and Research Institute, which manufactures many of the most advanced military aircraft for the People’s Liberation Army. “The main reason is the amazing demand in the market for drones after 9/11.”

Although surveillance drones have become widely used around the world, armed drones are more difficult to acquire.

Israel, the second-largest drone manufacturer after the United States, has flown armed models, but few details are available. India announced this year that it is developing ones that will fire missiles and fly at 30,000 feet. Russia has shown models of drones with weapons, but there is little evidence that they are operational.

Pakistan has said it plans to obtain armed drones from China, which has already sold the nation ones for surveillance. And Iran last summer unveiled a drone that Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad called the “ambassador of death” but whose effectiveness is still unproven, according to military analysts.

The United States is not yet threatened by any of these developments. No other country can match its array of aircraft with advanced weapons and sensors, coupled with the necessary satellite and telecommunications systems to deploy drones successfully across the globe.

“We are well ahead in having established systems actively in use,” said retired Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, the former deputy chief of staff for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance at the Air Force. “But the capability of other countries will do nothing but grow.”

Raising alarm

In recent conflicts, the United States has primarily used land-based drones, but it is developing an aircraft carrier-based version to deploy in the Pacific. Defense analysts say the new drone is partly intended to counter the long-range “carrier killer” missile that China is developing.

With the ascendance of China’s military, American allies in the Pacific increasingly see the United States as the main bulwark against rising Chinese power. And China has increasingly framed its military developments in response to U.S. capabilities.

A sea-based drone would give the United States the ability to fly three times the distance of a normal Navy fighter jet, potentially keeping a carrier group farther from China’s coast.

This possible use of U.S. drones in the Pacific has been noted with alarm in news reports in China as well as in North Korea’s state-run media.

There are similar anxieties in the United States over China’s accelerating drone industry. A report last November by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission noted that the Chinese military “has deployed several types of unmanned aerial vehicles for both reconnaissance and combat.”

In the pipeline, the report said, China has several medium- and high-altitude long-endurance drones, which could expand China’s options for long-range surveillance and attacks.

China’s rapid development has pushed its neighbors into action. After a diplomatic clash with China last fall over disputed territories in the South China Sea, Japan announced that it planned to send military officials to the United States to study how it operates and maintains its Global Hawk high-altitude surveillance drones. In South Korea, lawmakers this year accused China of hacking into military computers to learn about the country’s plans to acquire Global Hawk, which could peer into not only North Korea but also parts of China and other neighboring countries.

On top of the increasing anxieties of individual countries, there also are international concerns that some governments might not be able to protect these new weapons from hackers and terrorists. Sharkey, the University of Sheffield professor who also co-founded the International Committee for Robot Arms Control, noted that Iraqi insurgents, using a $30 piece of software, intercepted live feeds from U.S. drones; the video was later found on the laptop of a captured militant.

Relaxing U.S. export controls

But with China and other countries beginning to market their drones, the United States is looking to boost its sales by exploring ways to relax American export controls.

Vice Adm. William E. Landay III, director of the Defense Security Cooperation Agency overseeing foreign military sales, said at a Pentagon briefing recently that his agency is working on preapproved lists of countries that would qualify to purchase drones with certain capabilities. “If industry understands where they might have an opportunity to sell, and where they won’t, that’s useful for them,” Landay said.

General Atomics, the San Diego-based manufacturer of the U.S. Predator drones, has received approval to export to the Middle East and Latin America an unarmed, early-generation Predator, according to company spokeswoman Kimberly Kasitz. The company is now in talks with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt, among others, she said.

At the same time, U.S. officials have sought to limit where others sell their drones. After Israel sold an anti-radar attack drone to China, the Pentagon temporarily shut Israel out of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program to register its disapproval.

In 2009, the United States also objected to an Israeli sale of sophisticated drones to Russia, according to diplomatic cables released by the anti-secrecy group WikiLeaks. A smaller co-production deal was later brokered with the Russians, who bristled when Georgia deployed Israeli surveillance drones against its forces during the 2008 war between the two countries.

But for China, there are few constraints on selling. It has begun to show its combat drone prototypes at international air shows, including last month in Paris, where a Chinese manufacturer displayed a craft, called the Wing-Loong, that looked like a Predator knockoff. Because of how tightly China controls its military technology, it is unclear how far along the Wing-Loong or any of its armed drones are from actual production and operation, defense analysts say.

According to the Aviation Industry Corp. of China, it has begun offering international customers a combat and surveillance drone comparable to the Predator called the Yilong, or “pterodactyl” in English. Zhang, of the Chengdu Aircraft Design and Research Institute, said the company anticipates sales in Pakistan, the Middle East and Africa.

However, he and others displaying drones at a recent Beijing anti-terrorism convention played down the threat of increasing Chinese drone technology.

“I don’t think China’s drone technology has reached the world’s first-class level,” said Wu Zilei, from the China Shipbuilding Industry Corp., echoing an almost constant refrain. “The reconnaissance drones are okay, but the attack drones are still years behind the United States.”

But Richard Fisher, a senior fellow at the Washington-based International Assessment and Strategy Center, said such statements are routine and intended to deflect concern about the nation’s expanding military ambitions.

“The Chinese are catching up quickly. This is something we know for sure,” Fisher said. “We should not take comfort in some perceived lags in sensors or satellites capabilities. Those are just a matter of time.”

Staff researchers Julie Tate in Washington and Zhang Jie in Beijing contributed to this report.

Privacy issues hover over police drone use

By Peter Finn, Published: January 22

AUSTIN - The suspect's house, just west of this city, sat on a hilltop at the end of a steep, exposed driveway. Agents with the Texas Department of Public Safety believed the man inside had a large stash of drugs and a cache of weapons, including high-caliber rifles.

As dawn broke, a SWAT team waiting to execute a search warrant wanted a last-minute aerial sweep of the property, in part to check for unseen dangers. But there was a problem: The department's aircraft section feared that if it put up a helicopter, the suspect might try to shoot it down.

So the Texas agents did what no state or local law enforcement agency had done before in a high-risk operation: They launched a drone. A bird-size device called a Wasp floated hundreds of feet into the sky and instantly beamed live video to agents on the ground. The SWAT team stormed the house and arrested the suspect.

"The nice thing is it's covert," said Bill C. Nabors Jr., chief pilot with the Texas DPS, who in a recent interview described the 2009 operation for the first time publicly. "You don't hear it, and unless you know what you're looking for, you can't see it."

The drone technology that has revolutionized warfare in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan is entering the national airspace: Unmanned aircraft are patrolling the border with Mexico, searching for missing persons over difficult terrain, flying into hurricanes to collect weather data, photographing traffic accident scenes and tracking the spread of forest fires.

But the operation outside Austin presaged what could prove to be one of the most far-reaching and potentially controversial uses of drones: as a new and relatively cheap surveillance tool in domestic law enforcement.

For now, the use of drones for high-risk operations is exceedingly rare. The Federal Aviation Administration - which controls the national airspace - requires the few police departments with drones to seek emergency authorization if they want to deploy one in an actual operation. Because of concerns about safety, it only occasionally grants permission.

But by 2013, the FAA expects to have formulated new rules that would allow police across the country to routinely fly lightweight, unarmed drones up to 400 feet above the ground - high enough for them to be largely invisible eyes in the sky.

Such technology could allow police to record the activities of the public below with high-resolution, infrared and thermal-imaging cameras.

One manufacturer already advertises one of its small systems as ideal for "urban monitoring." The military, often a first user of technologies that migrate to civilian life, is about to deploy a system in Afghanistan that will be able to scan an area the size of a small town. And the most sophisticated robotics use artificial intelligence to seek out and record certain kinds of suspicious activity.

But when drones come to perch in numbers over American communities, they will drive fresh debates about the boundaries of privacy. The sheer power of some of the cameras that can be mounted on them is likely to bring fresh search-and-seizure cases before the courts, and concern about the technology's potential misuse could unsettle the public.

"Drones raise the prospect of much more pervasive surveillance," said Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst with the American Civil Liberties Union's Speech, Privacy and Technology Project. "We are not against them, absolutely. They can be a valuable tool in certain kinds of operations. But what we don't want to see is their pervasive use to watch over the American people."

The police are likely to use drones in tactical operations and to view clearly public spaces. Legal experts say they will have to obtain a warrant to spy on private homes.

FAA authorization

As of Dec. 1, according to the FAA, there were more than 270 active authorizations for the use of dozens of kinds of drones. Approximately 35 percent of these permissions are held by the Defense Department, 11 percent by NASA and 5 percent by the Department of Homeland Security, including permission to fly Predators on the northern and southern borders.

Other users are law enforcement agencies, including the FBI, as well as manufacturers and academic institutions.

For now, only a handful of police departments and sheriff's offices in the United States - including in Queen Anne's County, Md., Miami-Dade County, Fla., and Mesa County, Colo. - fly drones. They so do as part of pilot programs that mostly limit the use of the drones to training exercises over unpopulated areas.

Among state and local agencies, the Texas Department of Public Safety has been the most active user of drones for high-risk operations. Since the search outside Austin, Nabors said, the agency has run six operations with drones, all near the southern border, where officers conducted surveillance of drug and human traffickers.

Some police officials, as well as the manufacturers of unmanned aerial systems, have been clamoring for the FAA to allow their rapid deployment by law enforcement. They tout the technology as a tactical game-changer in scenarios such as hostage situations and high-speed chases.

Overseas, the drones have drawn interest as well. A consortium of police departments in Britain is developing plans to use them to monitor the roads, watch public events such as protests, and conduct covert urban surveillance, according to the Guardian newspaper. Senior British police officials would like the machines to be in the air in time for the 2012 Olympics in London.

"Not since the Taser has a technology promised so much for law enforcement," said Ben Miller of the Mesa County Sheriff's Office, which has used its drone, called a Draganflyer, to search for missing persons after receiving emergency authorization from the FAA.

Cost has become a big selling point. A drone system, which includes a ground operating computer, can cost less than $50,000. A new police helicopter can cost up to $1 million. As a consequence, fewer than 300 of the approximately 19,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States have an aviation capability.

"The cost issue is significant," said Martin Jackson, president of the Airborne Law Enforcement Association. "Once they open the airspace up [to drones], I think there will be quite a bit of demand."

The FAA is reluctant to simply open up airspace, even to small drones. The agency said it is addressing two critical questions: How will unmanned aircraft "handle communication, command and control"? And how will they "sense and avoid" other aircraft, a basic safety element in manned aviation?

Military studies suggest that drones have a much higher accident rate than manned aircraft. That is, in part, because the military is using drones in a battlefield environment. But even outside war zones, drones have slipped out of their handlers' control.

In the summer, a Navy drone, experiencing what the military called a software problem, wandered into restricted Washington airspace. Last month, a small Mexican army drone crashed into a residential yard in El Paso.

There are also regulatory issues with civilian agencies using military frequencies to operate drones, a problem that surfaced in recent months and has grounded the Texas DPS drones, which have not been flown since August.

"What level of trust do we give this technology? We just don't yet have the data," said John Allen, director of Flight Standards Service in the FAA's Office of Aviation Safety. "We are moving cautiously to keep the National Airspace System safe for all civil operations. It's the FAA's responsibility to make sure no one is harmed by [an unmanned aircraft system] in the air or on the ground."

Officials in Texas said they supported the FAA's concern about safety.

"We have 23 aircraft and 50 pilots, so I'm of the opinion that FAA should proceed cautiously," Nabors said.

Legal touchstones

Much of the legal framework to fly drones has been established by cases that have examined the use of manned aircraft and various technologies to conduct surveillance of both public spaces and private homes.

In a 1986 Supreme Court case, justices were asked whether a police department violated constitutional protections against illegal search and seizure after it flew a small plane above the back yard of a man suspected of growing marijuana. The court ruled that "the Fourth Amendment simply does not require the police traveling in the public airways at this altitude to obtain a warrant in order to observe what is visible to the naked eye."

In a 2001 case, however, also involving a search for marijuana, the court was more skeptical of police tactics. It ruled that an Oregon police department conducted an illegal search when it used a thermal imaging device to detect heat coming from the home of an man suspected of growing marijuana indoors.

"The question we confront today is what limits there are upon this power of technology to shrink the realm of guaranteed privacy," Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in the 2001 case.

Still, Joseph J. Vacek, a professor in the Aviation Department at the University of North Dakota who has studied the potential use of drones in law enforcement, said the main objections to the use of domestic drones will probably have little to do with the Constitution.

"Where I see the challenge is the social norm," Vacek said. "Most people are not okay with constant watching. That hover-and-stare capability used to its maximum potential will probably ruffle a lot of civic feathers."

At least one community has already balked at the prospect of unmanned aircraft.

The Houston Police Department considered participating in a pilot program to study the use of drones, including for evacuations, search and rescue, and tactical operations. In the end, it withdrew.

A spokesman for Houston police said the department would not comment on why the program, to have been run in cooperation with the FAA, was aborted in 2007, but traffic tickets might have had something to do with it.

When KPRC-TV in Houston, which is owned by The Washington Post Co., discovered a secret drone air show for dozens of officers at a remote location 70 miles from Houston, police officials were forced to call a hasty news conference to explain their interest in the technology.

A senior officer in Houston then mentioned to reporters that drones might ultimately be used for recording traffic violations.

Federal officials said support for the program crashed.

Staff researcher Julie Tate contributed to this report.

With Air Force's Gorgon Drone 'we can see everything'

By Ellen Nakashima and Craig Whitlock

Washington Post Staff Writers

Sunday, January 2, 2011; 12:09 AM

In ancient times, Gorgon was a mythical Greek creature whose unblinking eyes turned to stone those who beheld them. In modern times, Gorgon may be one of the military's most valuable new tools.

This winter, the Air Force is set to deploy to Afghanistan what it says is a revolutionary airborne surveillance system called Gorgon Stare, which will be able to transmit live video images of physical movement across an entire town.

The system, made up of nine video cameras mounted on a remotely piloted aircraft, can transmit live images to soldiers on the ground or to analysts tracking enemy movements. It can send up to 65 different images to different users; by contrast, Air Force drones today shoot video from a single camera over a "soda straw" area the size of a building or two.

With the new tool, analysts will no longer have to guess where to point the camera, said Maj. Gen. James O. Poss, the Air Force's assistant deputy chief of staff for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. "Gorgon Stare will be looking at a whole city, so there will be no way for the adversary to know what we're looking at, and we can see everything."

Questions persist, however, about whether the military has the capability to sift through huge quantities of imagery quickly enough to convey useful data to troops in the field.

Officials also acknowledge that Gorgon Stare is of limited value unless they can match it with improved human intelligence - eyewitness reports of who is doing what on the ground.

The Air Force is exponentially increasing surveillance across Afghanistan. The monthly number of unmanned and manned aircraft surveillance sorties has more than doubled since last January, and quadrupled since the beginning of 2009.

Indeed, officials say, they cannot keep pace with the demand.

"I have yet to go a week in my job here without having a request for more Air Force surveillance out there," Poss said.

But adding Gorgon Stare will also generate oceans of more data to process.

"Today an analyst sits there and stares at Death TV for hours on end, trying to find the single target or see something move," Gen. James E. Cartwright, the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said at a conference in New Orleans in November. "It's just a waste of manpower."

The hunger for these high-tech tools was evident at the conference, where officials told several thousand industry and intelligence officials they had to move "at the speed of war." Cartwright pressed for solutions, even partial ones, in a year or less.

Increased U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan killing few high-value militants

By Greg Miller

Washington Post Staff Writer

Monday, February 21, 2011

CIA drone attacks in Pakistan killed at least 581 militants last year, according to independent estimates. The number of those militants noteworthy enough to appear on a U.S. list of most-wanted terrorists: two.

Despite a major escalation in the number of unmanned Predator strikes being carried out under the Obama administration, data from government and independent sources indicate that the number of high-ranking militants being killed as a result has either slipped or barely increased. [That's odd! I thought that any brown skinned foreigner killed by the American Empire was a high value target, even if it was a 9 year old girl? After all the generals need some good propaganda to sell the war to the American people!]

Even more generous counts - which indicate that the CIA killed as many as 13 "high-value targets" - suggest that the drone program is hitting senior operatives only a fraction of the time.

After a year in which the CIA carried out a record 118 drone strikes, costing more than $1 million apiece, the results have raised questions about the purpose and parameters of the campaign. [Wow! It costs $1 million bucks for every barefoot poppy farmer killed, which we pretend is a threat to the security of the American Empire]

Senior Pakistani officials recently asked the Obama administration to put new restraints on a targeted-killing program that the government in Islamabad has secretly authorized for years.

The CIA is increasingly killing "mere foot soldiers," a senior Pakistani official said, adding that the issue has come up in discussions in Washington involving President Asif Ali Zardari. The official said Pakistan has pressed the Americans "to find better targets, do it more sparingly and be a little less gung-ho."

Experts who track the strikes closely said a program that began with intermittent lethal attacks on al-Qaeda leaders has evolved into a campaign that seems primarily focused on lower-level fighters. Peter Bergen, a director at the New America Foundation, said data on the strikes indicate that 94 percent of those killed are lower-level militants. [Which means it now costs $20 million for each alleged high value target murdered by the American Empire, if the other 19 killed are just low level Muslim rag heads!]

"I think it's hard to make the case that the 94 percent cohort threaten the United States in some way," Bergen said. "There's been very little focus on that question from a human rights perspective. Targeted killings are about leaders - it shouldn't be a blanket dispensation."

Even former CIA officials who describe the drone program as essential said they have noted how infrequently they recognized the names of those killed during the barrage of strikes in the past year.

The CIA declined to comment on a program that the agency refuses to acknowledge publicly. But U.S. officials familiar with drone operations said the strikes are hitting important al-Qaeda operatives and are critical to keeping the United States safe.

"This effort has evolved because our intelligence has improved greatly over the years, and we're able to identify not just senior terrorists, but also al-Qaeda foot soldiers who are planning attacks on our homeland and our troops in Afghanistan," said a U.S. official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the classified program.

"We would be remiss if we didn't go after people who have American blood on their hands," the official said. "To use a military analogy, if you're only going after the generals, you're likely to be run over by tanks."

The data about the drone strikes provide a blurry picture at best, because of the reliance on Pakistani media reports and anonymous accounts from U.S. government sources. There are also varying terms used to describe high-value targets, with no precise definitions.

Even so, the data suggest that the ratio of senior terrorism suspects being killed is declining at a substantial rate. The New America Foundation recently concluded that 12 "militant leaders" were killed by drone strikes in 2010, compared with 10 in 2008. The number of strikes soared over that period, from 33 to 118.

The National Counterterrorism Center, which tracks terrorist leaders who are captured or killed, counts two suspects on U.S. most-wanted lists who died in drone strikes last year. They are Sheik Saeed al-Masri, al-Qaeda's No. 3, and Ahmed Mohammed Hamed Ali, who was indicted in the 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in East Africa before serving as al-Qaeda's chief of paramilitary operations in Afghanistan.

According to the NCTC, two senior operatives also were killed in drone strikes in each of the preceding years.

When the Predator was first armed, it was seen as a weapon uniquely suited to hunt the highest of high-value targets, including Osama bin Laden and his deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri. For years, the program was relatively small in scale, with intermittent strikes.

U.S. officials cite multiple reasons for the change in scope, including a proliferation in the number of drones and CIA informants providing intelligence on potential targets. The unmanned aircraft have not gotten the agency any closer to bin Laden but are regarded as the most important tool for keeping pressure on al-Qaeda's middle and upper ranks.

Officials cite other factors as well, including a shift in CIA targeting procedures, moving beyond the pursuit of specific individuals to militants who meet secret criteria the agency refers to as "pattern of life."

In its early years, the drone campaign was mainly focused on finding and killing militants whose names appeared on a list maintained by the CIA's Counterterrorist Center. But since 2008, the agency has increasingly fired missiles when it sees certain "signatures," such as travel in or out of a known al-Qaeda compound or possession of explosives.

"It's like watching 'The Sopranos': You know what's going on in the Bada Bing," said a former senior U.S. intelligence official, referring to the fictional New Jersey strip club used for Mafia meetings in the HBO television series.

Finally, CIA drone strikes that used to focus almost exclusively on al-Qaeda are increasingly spread across an array of militant groups, including Taliban networks responsible for plots against targets in the United States as well as attacks on troops in Afghanistan.

In recent weeks, the drone campaign has fallen strangely silent. The last reported strike occurred Jan. 23 south of the Pakistani city of Miram Shah, marking the longest pause in the program since vast areas of Pakistan were affected by floods last year. Speculation in that country has centered on the possibility that the CIA is holding fire until a U.S. security contractor accused of fatally shooting two Pakistani men last month is released from a jail in Lahore.

U.S. officials deny that has been a factor and describe the lull as a seasonal slowdown in a program expected to resume its accelerated pace.

The intensity of the strikes has caused an increase in the number of fatalities. The New America Foundation estimates that at least 607 people were killed in 2010, which would mean that a single year has accounted for nearly half of the number of deaths since 2004, when the program began.

Overall, the foundation estimates that 32 of those killed could be considered "militant leaders" of al-Qaeda or the Taliban, or about 2 percent.

The problem does not appear to be one of precision. Even as the number of strikes has soared, civilian casualty counts have dropped. The foundation estimates that the civilian fatality rate plunged from 25 percent in 2004 to 6 percent in 2010. The CIA thinks it has not killed a single civilian in six months. [Well that's because every brown skinned 6 year old girl killed by drones was considered a dangerous terrorist who could kill Obama, if here mother replaced her rag doll with an AK-47, and shipped her off to Washington D.C.]

Defenders of the program emphasize such statistics and say that empirical evidence suggests that the ramped-up targeting of lesser-known militants has helped to keep the United States safe. [Yea, you never know when a 6 year old child in Pakistan is going to sneak into the USA and attempt to assassinate Obama! Kick ass first and kill terrorists, no need to let your brain start thinking and use logic and reason.]

The former high-ranking U.S. intelligence official said the drone campaign has degraded not only al-Qaeda's leadership, but also the caliber of the organization's plots. [Yea, and it has murdered a lot of innocent 6 year old children.]

Thwarted attacks traced back to Pakistan over the past two years - including a botched attempt to blow up a vehicle in New York's Times Square - are strikingly amateurish compared with the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and other airline plots that followed, the argument goes.

"Pawns matter," the former official said. "It's always more dramatic to take the bishop, and, if you can find them, the king and queen."

Staff writer Karen DeYoung and staff researcher Julie Tate contributed to this report.

The other eyes in the sky

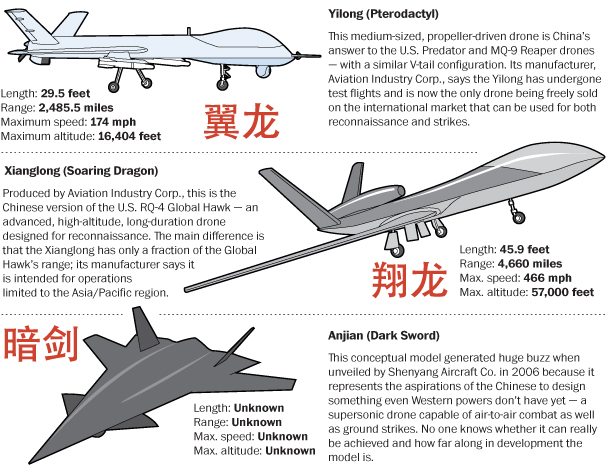

In recent years, China has pumped massive amounts of money and engineering brainpower into drones technology, a field dominated by the United States and Israel. No one knows which Chinese models are actually in production and operation, but Chinese companies have displayed several in development that rival current U.S. drones.

'Hands-free' landing is a step toward unmanned naval flight

By Bill Sizemore

The Virginian-Pilot

July 9, 2011

Are the days of "Top Gun" coming to an end?

Not yet. But the Navy moved a step closer to a new era of unmanned carrier-based aerial combat last weekend.

Aboard the Norfolk-based aircraft carrier Dwight D. Eisenhower off the Virginia coast Saturday, an F/A-18D Hornet, modified to emulate an unmanned aircraft, made its first carrier touchdown without a pilot's guiding hands.

A pilot and a flight officer were in the cockpit in case human intervention was needed, but the landing was "hands-free" - controlled by a linked computer network on the ship and the plane.

The F/A-18D fighter jet was a stand-in for the X-47B, a bat-winged, fighter-sized unmanned aircraft under development by Northrop Grumman Corp. as part of the Navy's Unmanned Combat Air System Demonstration program.

The pilot of the surrogate plane, Lt. Jeremy DeBons, said the hands-free landing was in one sense an incremental step, because fighter jets are already capable of being coupled with a carrier's computer system for assistance in touchdowns.

Still, DeBons said, because this is a new system, extra vigilance was in order.

"As any test pilot will tell you, we're always on guard," he said. "It's not only hands-free. It's hands very close to the controls if we have to take over."

The successful automated landing on the Eisenhower was "a very significant step" toward eventual use of unmanned drones on carriers, Rear Adm. Bill Shannon, the program executive officer, said in a conference call with reporters Thursday.

That doesn't mean the end of manned naval flight is anywhere on the horizon, said Capt. Jaime Engdahl, the program manager.

"That is not the goal," Engdahl said. "The Navy's goal is to seamlessly integrate unmanned systems into the fleet. It's really in the gaps - where it can complement manned assets and expand the Navy's capability in intelligence collection, surveillance and reconnaissance."

For instance, he said, one of the gaps the Navy hopes to fill with drones is in long-duration flights that are beyond the capacity of a human crew.

Still, there is little doubt that Navy drones eventually will move beyond a surveillance role, said Peter Singer, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank, who has written a book on automated warfare.

The Air Force's Predator drones were originally designed for surveillance, he noted, but are now widely used for dropping bombs. There is no reason Navy drones couldn't be used the same way or even for air-to-air combat, he said.

Human pilots aren't going away anytime soon, but the dawn of unmanned naval flight portends a changing role for them, Singer said.

"We previously judged the value of the aviator by technical skill - particularly at carrier deck landings," he said. "I think increasingly we're going to judge the human aviator not so much on quick reactions in their fingertips but on that mushy gray thing in their skull and that pulsating thing in their chest.

"We're going to judge them less on things like carrier deck landings and more on things like when is it proper to shoot or not - a sense of strategy, a sense of right and wrong, a sense of awareness."

There's also little doubt that the changes will come sooner rather than later, Singer said. He used a historical anecdote to illustrate the point.

On Oct. 9, 1903, The New York Times predicted that flying machines would take "one to ten million years" to develop. That same day, the Wright brothers began assembling their first airplane. Seven years later, Eugene Ely flew off a wooden platform built on the bow of the cruiser Birmingham in Hampton Roads, and the era of naval aviation was born.

Modifications to accommodate the unmanned system on the Eisenhower began last fall. Initial surrogate testing, which proved the system was ready, took place during the ship's sea trials the week of June 13.

Flight testing of the X-47B unmanned aircraft is under way at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., and will move to Patuxent River Naval Air Station in Maryland later this year.

The Navy is aiming to land the X-47B on a carrier in 2013.

Bill Sizemore, (757) 446-2276, bill.sizemore@pilotonline.com

Lawmaker: Iran shot down unmanned US spy plane

By ALI AKBAR DAREINI - Associated Press

TEHRAN, Iran (AP) — Iran's Revolutionary Guard shot down an unmanned U.S. spy plane that was trying to gather information on an underground uranium enrichment site, a state-owned news site said Wednesday.

Lawmaker Ali Aghazadeh Dafsari said the drone was flying over the Fordo uranium enrichment site near the holy city of Qom in central Iran, the state TV-run Youth Journalists Club said.

The report did not say when the plane was shot down.

Iran is locked in a dispute with the U.S. and its allies over Tehran's disputed nuclear program, which the West believes aims to develop nuclear weapons. Iran denies the accusations, saying its nuclear program is aimed at generating electricity and producing isotopes to treat medical patients.

Long kept secret, the Fordo site is built next to a military complex to protect it in case of attack. Iran only acknowledged Fordo's existence after Western intelligence agencies identified it in September 2009. The facility is reportedly located 295 feet (90 meters) underneath a mountain.

Iran says it is planning to install advanced centrifuges at Fordo to speed up its nuclear activities.

U.S. nuclear experts say by increasing the enrichment level and its stock of nearly 20 percent low-enriched uranium, Iran could reach a "break out" capability that would allow it to make enough weapon-grade uranium for a nuclear weapon.

Iran has claimed to shoot down U.S. spy planes in the past. Earlier this month, Iranian military officials showed Russian experts several U.S. drones they said were shot down in recent years.

Here is an article about a company in Mesa Arizona that makes drones to help the government kill people. That company is:

Thorpe Seeop CorporationTheir web page is here.

1045 E. McKellips

Mesa, AZ

85203

Even more articles on radio controlled drones.